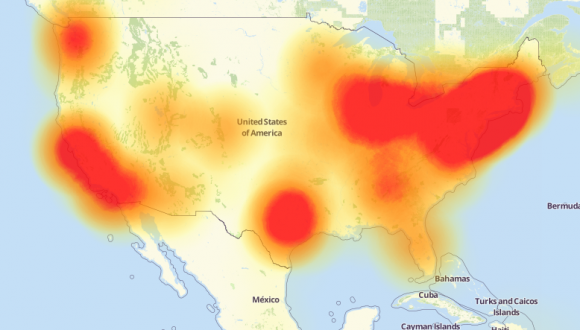

A massive and sustained Internet attack that has caused outages and network congestion today for a large number of Web sites was launched with the help of hacked “Internet of Things” (IoT) devices, such as CCTV video cameras and digital video recorders, new data suggests.

Earlier today cyber criminals began training their attack cannons on Dyn, an Internet infrastructure company that provides critical technology services to some of the Internet’s top destinations. The attack began creating problems for Internet users reaching an array of sites, including Twitter, Amazon, Tumblr, Reddit, Spotify and Netflix.

At first, it was unclear who or what was behind the attack on Dyn. But over the past few hours, at least one computer security firm has come out saying the attack involved Mirai, the same malware strain that was used in the record 620 Gpbs attack on my site last month. At the end September 2016, the hacker responsible for creating the Mirai malware released the source code for it, effectively letting anyone build their own attack army using Mirai.

Mirai scours the Web for IoT devices protected by little more than factory-default usernames and passwords, and then enlists the devices in attacks that hurl junk traffic at an online target until it can no longer accommodate legitimate visitors or users.

According to researchers at security firm Flashpoint, today’s attack was launched at least in part by a Mirai-based botnet. Allison Nixon, director of research at Flashpoint, said the botnet used in today’s ongoing attack is built on the backs of hacked IoT devices — mainly compromised digital video recorders (DVRs) and IP cameras made by a Chinese hi-tech company called XiongMai Technologies. The components that XiongMai makes are sold downstream to vendors who then use it in their own products.

“It’s remarkable that virtually an entire company’s product line has just been turned into a botnet that is now attacking the United States,” Nixon said, noting that Flashpoint hasn’t ruled out the possibility of multiple botnets being involved in the attack on Dyn.

“At least one Mirai [control server] issued an attack command to hit Dyn,” Nixon said. “Some people are theorizing that there were multiple botnets involved here. What we can say is that we’ve seen a Mirai botnet participating in the attack.”

As I noted earlier this month in Europe to Push New Security Rules Amid IoT Mess, many of these products from XiongMai and other makers of inexpensive, mass-produced IoT devices are essentially unfixable, and will remain a danger to others unless and until they are completely unplugged from the Internet.

That’s because while many of these devices allow users to change the default usernames and passwords on a Web-based administration panel that ships with the products, those machines can still be reached via more obscure, less user-friendly communications services called “Telnet” and “SSH.”

Telnet and SSH are command-line, text-based interfaces that are typically accessed via a command prompt (e.g., in Microsoft Windows, a user could click Start, and in the search box type “cmd.exe” to launch a command prompt, and then type “telnet” to reach a username and password prompt at the target host).

“The issue with these particular devices is that a user cannot feasibly change this password,” Flashpoint’s Zach Wikholm told KrebsOnSecurity. “The password is hardcoded into the firmware, and the tools necessary to disable it are not present.

“The issue with these particular devices is that a user cannot feasibly change this password,” Flashpoint’s Zach Wikholm told KrebsOnSecurity. “The password is hardcoded into the firmware, and the tools necessary to disable it are not present. Even worse, the web interface is not aware that these credentials even exist.”

Flashpoint’s researchers said they scanned the Internet on Oct. 6 for systems that showed signs of running the vulnerable hardware, and found more than 515,000 of them were vulnerable to the flaws they discovered.

“I truly think this IoT infrastructure is very dangerous on the whole and does deserve attention from anyone who can take action,” Flashpoint’s Nixon said.

It’s unclear what it will take to get a handle on the security problems introduced by millions of insecure IoT devices that are ripe for being abused in these sorts of assaults.

As I noted in The Democratization of Censorship, to address the threat from the mass-proliferation of hardware devices such as Internet routers, DVRs and IP cameras that ship with default-insecure settings, we probably need an industry security association, with published standards that all members adhere to and are audited against periodically.

The wholesalers and retailers of these devices might then be encouraged to shift their focus toward buying and promoting connected devices which have this industry security association seal of approval. Consumers also would need to be educated to look for that seal of approval. Something like Underwriters Laboratories (UL), but for the Internet, perhaps.

Until then, these insecure IoT devices are going to stick around like a bad rash — unless and until there is a major, global effort to recall and remove vulnerable systems from the Internet. In my humble opinion, this global cleanup effort should be funded mainly by the companies that are dumping these cheap, poorly-secured hardware devices onto the market in an apparent bid to own the market. Well, they should be made to own the cleanup efforts as well.

Devices infected with Mirai are instructed to scour the Internet for IoT devices protected by more than 60 default usernames and passwords. The entire list of those passwords — and my best approximation of which firms are responsible for producing those hardware devices — can be found at my story, Who Makes the IoT Things Under Attack.